In Defence of Qualitative Research

I had to move from Psychology to Computer Science to appreciate the importance of asking people, “Why”?

Learning to Appreciate Quality within Qualitative

Quantitative vs Qualitative. I remember the debate from my A level Psychology classes back in college. Regurgitating the rote-learnt answer for the pros and cons of both, robotically writing out my answer to be as concise as possible. How quant is reliable but not necessarily valid (sure, 83% of your sample said they liked the green option, but does it matter if you don’t know why?), how qual gives rich data but can be subjective (maybe a participant said they think green is soothing, but is that just them, or everyone?). The answer always led to a combination of the two being the best solution, where you can be sure you’ve found objective evidence of a trend but also a better chance of understanding it (e.g. people responded most strongly to green because it reminds them of growth). The full marks came and went and I thought little of it.

Fast forward to my undergraduate degree in Psychology. The study of people enthralled me early on, especially in terms of social interactions. Sometimes, not even socially with other people, hence my current interest in people interacting with computer games. The topics covered in undergrad are vast, from depression to vision to memory, each requiring their own different analysis of data. But they did have one thing in common; a heavy bias towards quantitative methods.

Analysis of genes to uncover what might increase the risk of depression, using eye tracking equipment to measure where people focus in an image, asking people to recall as many items as possible from a list. Always numbers, always clean, cold-cut facts to debate profusely in academic journals. I didn’t realise at the time how the focus on numbers made the concept of words begin to fade, and over time I internalised a mild distrust towards studies that dared to break the trend.

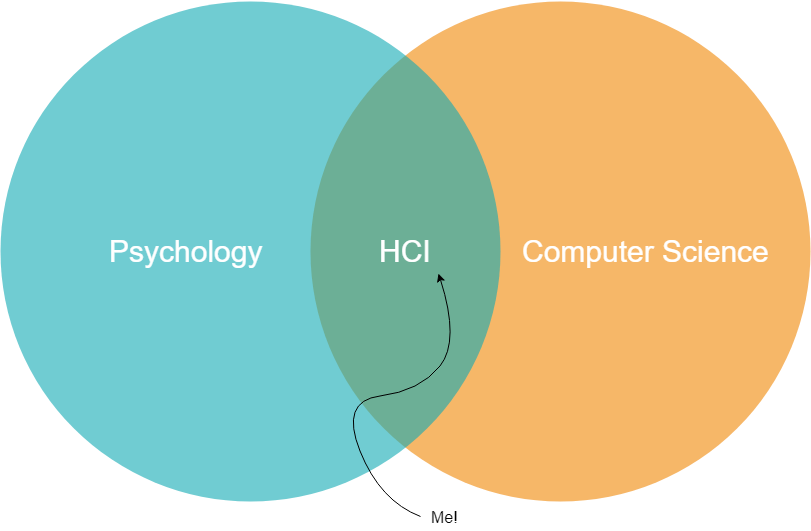

After my 4 happy years pursuing Psychology, I shifted gears a little to focus on gaming behaviour, which required a sidestep closer to the field of Computer Science. I was lucky enough to find a PhD course looking specifically at gaming, and I chased it with a burning passion. This is where I am now, currently in my first year of the course. I’m still very much on the people side of things, perhaps i’ll never be able to truly forget my roots. Landing squarely in the middle ground of the two fields at Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), I found a new home, but also a very foreign landscape.

Very simplistically of course, there’s many other factors and disciplines involved. But this is how I like to visualise it.

Computer Scientists don’t run experiments like Psychologists do. Understandably, as the most common ‘participant’ for them are computers, not people. It was daunting to change fields, but HCI provided the perfect blend of unexplored territory but familiar home ground (personality differences? Survey data? Sign me up). I want to understand how people make choices in open world games, and why. People surely must have preferences, but what are they? And how are they influenced? I have a lot of questions, and not a lot of answers.

I’m lucky to have a supervisor that’s been working in the field of research methods and HCI for over 20 years, and I remember approaching him about how to conduct my work. I had loads of ideas for surveys, game data, fancy techniques ready at my fingertips to find interesting results. But I wasn’t sure how i’d know if I was asking the right questions, using the right tools. What if my theories were almost correct, but not quite? How should I study open worlds, when I don’t fully know what it means to my demographic?

It was then that my supervisor gave me the simplest, yet mind-altering answer of my early academic career.

“Just ask them.”

I had to pause for a few seconds. Ask them? Just, let them talk to me? It felt like a short-circuit in my brain; surely the solution couldn’t be that simple? But he was right. If you want to understand why people do what they do, the easiest way is to simply, ask.

It felt like a taboo had been broken. All the years of silently doubting qualitative work, the heavy focus on numbers and statistics and reliability measures. They had tried to teach me its importance all the way back in college but it had been meaningless, just a bland answer to pass a test. Here, in the real world of research, I finally understood.

Since then i’ve started diving into qualitative methods, and now at the start of conducting my own interviews, I really do appreciate just how rich the data provided is. The mountains of audio files i’m currently wading through have so much opinion and explanation and pure human thought that it’s almost overwhelming. How could I have been so blind for so long? Why had I cut off this incredible side of research without giving it a chance to speak for itself?

Perhaps my experiences with Psychology are not in line with the average perception regarding the quality of qualitative research (a small sample size still does have its downsides!). Perhaps the departments I’ve frequented were more heavily quantitative-focused, more blinkered towards the need to be seen as a “real science” (yes, we are aware we’re the butt end of the joke when it comes to our credentials). Maybe I simply disregarded qualitative on my own accord.

But I think in the pursuit of being recognised as a hard science worthy of respect, Psychology has forgotten – or at the least is in danger of forgetting – that the focus is on people, and people are so much more than 0s and 1s. The irony is I had to change fields to realise it.